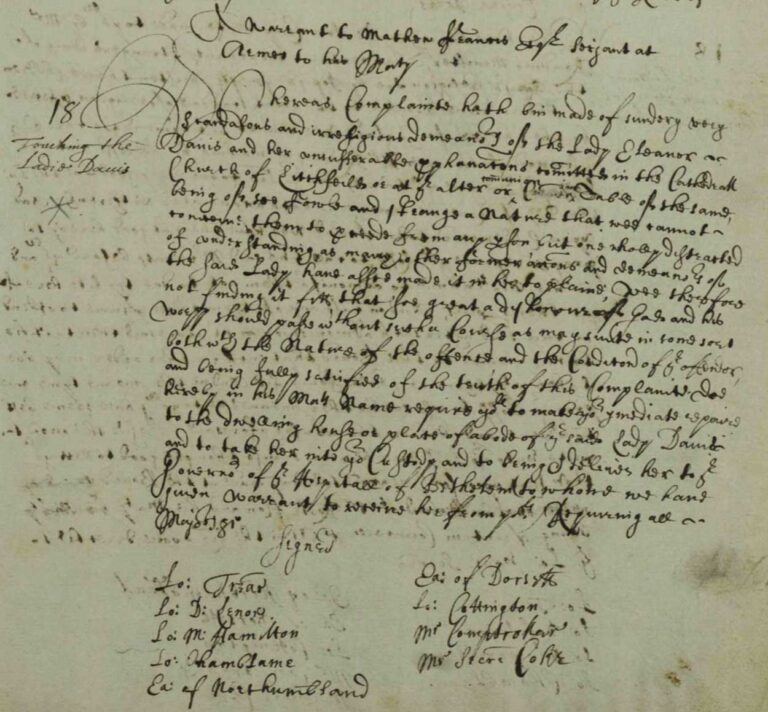

On 18 December 1636, the Privy Council register recorded that a woman had committed ‘insufferable profanations’ in the cathedral at Lichfield in Staffordshire.

Her offences were ‘of so foul and strange a nature that we cannot conceive them to proceed from any person but one wholly distracted of understanding’. She was committed to Bethlem Hospital (now usually known as Bedlam) for one of many periods of incarceration she was to experience during her lifetime.

The offender was born Lady Eleanor Touchet, but was often identified with the surnames of Davies or Douglas (her first and second husbands) or Audley (her father’s title of nobility).

Following a vision she experienced in 1625, she announced herself to be a messenger from the biblical prophet Daniel, informing the king and Parliament about the forthcoming Day of Judgement, which she anticipated would take place in 1645. She also started to prophesy events specific to individuals around her, such as the death of her first husband. She published pamphlets in support of her messages, and from then on, regularly ran into conflict with the authorities.

‘Abominable, stinking, greasy…’

Even before she took on the role of prophet, there is evidence that Lady Eleanor was involved in disputes with other members of the society in which she circulated. These came to a head in 1622, when we know of at least three clashes. Records of a Chancery suit brought by her and her husband against Thomas Leigh, concerning a bracelet or chain of small pearls, suggest she was prepared to turn to litigation over relatively petty matters. That same year a dispute with Lady Jacob was heard in the court of Star Chamber. Its subject, according to the correspondent John Chamberlain, was said to be ‘womanish brabbes’, probably meaning frivolous actions at law.

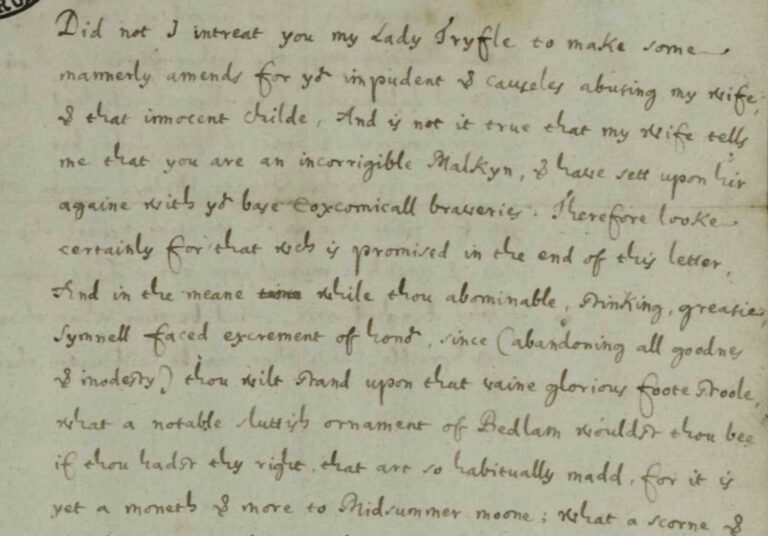

Lady Eleanor also managed to offend Christopher Brooke that same year, a copy of whose vitriolic, scatological attack on her in return made its way into the Conway Papers, which are now held as part of the State Papers. The page and a half of non-stop insults included references to her as an ‘abominable, stinking, greasy, simnel-faced excrement of honour’. Unusually for the State Papers, a second copy of the letter in a 19th-century hand is held alongside the earlier copy, suggesting that this text may have been circulated among like-minded critics, perhaps both contemporaneously and subsequently.

Although these cases could indicate that Lady Eleanor was especially quarrelsome, her biographer, Esther Cope, points out this was a time when tensions were running high at court, with the elevation of the Duke of Buckingham as the favourite of the King. It was also a time when multiple courts were available for those prepared to seek justice for themselves.

The power of anagrams

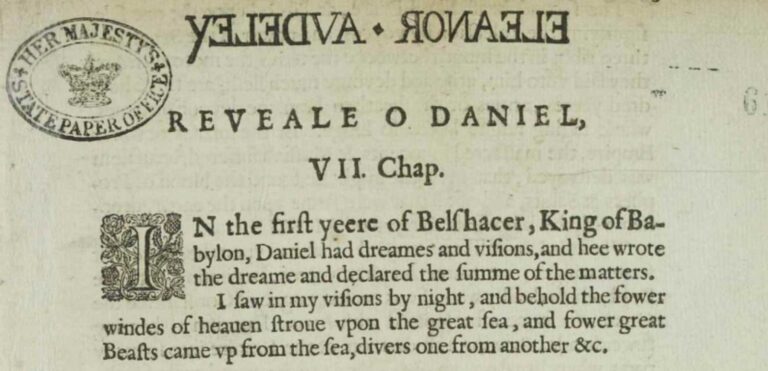

Lady Eleanor had a strong belief in the power of anagrams to uncover hidden meanings – an exercise made easier by the fluid spellings used in this period and her multiple names. Calling herself ‘Eleanor Audeley’ allowed her to interpret her name as REVEAL O DANYEL (helped by the interchangeable use of ‘v’ and ‘u’ at that date). She also addressed King Charles (Stuart) as AL TRUTHS CESAR in the early days of her optimism about his reign.

Unfortunately, others could also manipulate words, with Sir John Lambe, Dean of Arches producing his own anagram of Dame Eleanor Davies – ‘never so mad a ladie’.

Challenging authority

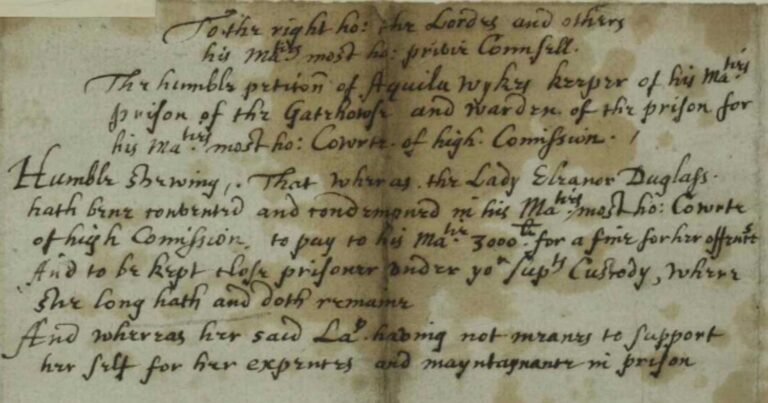

Lady Eleanor’s first stint in prison followed on from her appearance before the court of High Commission (otherwise known as the Commissioners of Ecclesiastical Causes) in 1633. She was found guilty of having printed her prophecies in Amsterdam and smuggled them back into the country. She was fined the enormous sum of £3,000 (the equivalent of £360,000 today) and was imprisoned on non-payment until 1635. Few records survive from this court, which was abolished in 1641, but those that do indicate the use of very large fines for some high-profile cases.

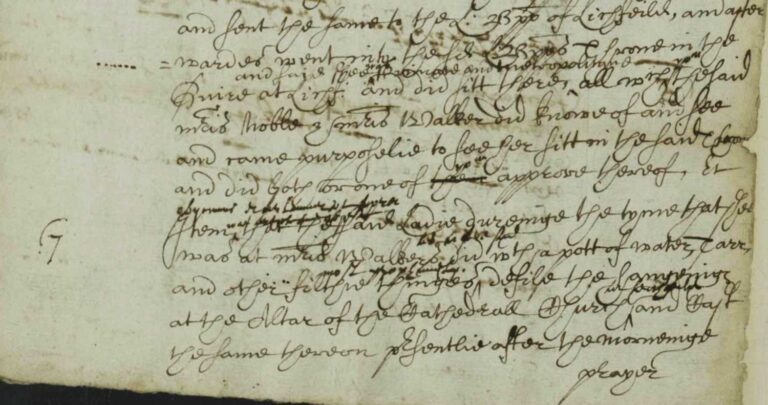

Just a year after her release, the events in Lichfield Cathedral in 1636 mentioned at the start of this blog were the culmination of a number of acts of protest carried out by Lady Eleanor and some female acquaintances.

They were troubled by what they saw as the use of Catholic ceremonial practices in the Church of England, including the moving and railing in of the communion table and the use of hierarchical seating patterns. Declaring herself ‘Primate and Metropolitan’ (i.e. archbishop), Lady Eleanor sat on the bishop’s throne and also attacked the new altar hangings with a mixture of tar, hot wheat and starch.

Lady Eleanor was to remain in Bedlam until 1638, when she was transferred to the Tower of London. From there, she was released into her son-in-law’s care in 1640. She carried on writing and publishing prophetic pamphlets for the rest of her life, with fewer obstacles posed by the state as it entered its own period of profound disruption with the Civil Wars and Commonwealth government. However, she was imprisoned two or three more times for debt and her publications.

Lady Eleanor certainly provoked some strong passions in her life, leading to both husbands destroying her papers, Archbishop Laud burning her pamphlets and the outburst from Christopher Brooke. However, many women stood by her, including initial support from Queen Henrietta Maria and the king’s sister, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, and lifelong support from her daughter, Lucy Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

Further reading

Esther S. Cope, Handmaid of the Holy Spirit: Dame Eleanor Davies, Never Soe Mad a Ladie (University of Michigan Press, 1992)

Diane Watt, ‘Davies, Lady Eleanor’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2008)

Lady Eleanor is a fascinating figure and an important writer not always treated with the sympathy she merits. In his ODNB entry on her first husband, Sean Kelsey cites Hans S. Pawlisch’s Sir John Davies and the Conquest of Ireland (1985): ‘From that time until his death in 1626, Davies suffered the uncomfortable experience of staring across the breakfast table at a hopelessly insane wife dressed in mourning’, a sentence that survived intact from Pawlisch’s 1981 PhD thesis. Conversely, Diane Watt, in her ODNB entry says of this match: ‘At the age of nineteen [Eleanor] married the poet and attorney-general for Ireland Sir John Davies (bap. 1569, d. 1626), who was not only more than twice her age but also had a violent temper and was, according to his contemporaries, ugly and exceedingly overweight.’ Touché!

She owned Rectory Manor in the village of Pirton Hertfordshire. We have an article about her on our website http://www.pirtonhistory.org.uk

https://pirtonhistory.org.uk/studies/lady-eleanor-davies-of-rectory-manor/

This is an interesting read. As someone who writes historical fiction, I plan to research this further. Thanks for posting.

Your insight into this lady is amazing and is so well realised with all the documents supporting it all.

Thank you

To read nearly 400pp of transcribed “Prophecies” + informative introduction please see: Prophetic Writings of Lady Eleanor Davies (by Esther S. Cope).

ISBN: 0-19-508717-8 paper

Lady Eleanor Davies

Lady Eleanor Davies was a hummingbird with the eyes

and talons of an eagle, and so became a bird of prey;

her Prophecies were composed with an iron will

and a generator-driven, swan-feather quill,

sometimes written in invisible ink

to confound the censors and detractors.

Her critical writings were condemned by thieves

of innocence, magistrates and misogynists,

but lauded by seekers of Truth;

she produced a river of anti-monarchy

vitriolic anagrams in stream-of-conscious style

containing sincere idea in both poetry and bile.

She once enquired of the King’s minions: Would

his Majesty’s invisible clothes be suitable apparel

to dress the Queen’s naked swans ? Her magnificent

obsession finally drove Eleanor to the brink of insanity,

her mystical visions losing literary clarity

and form, but cutting, always cutting, to the quick.

Eleanor Davies (1590 – 1652)

Eleanor Audeley = Reveal O Daniel:

Anagram (with some literary licence) by Mrs Eleanor Davies, c. 1620

Dame Eleanor Davies = Never soe mad a ladie:

Composed in court by The Dean of Arches, 1633

Lady Eleanor Davies = A lady reasoned evil

The author of this poem, 2023